Clara Haras Strahl: Transcribed from a videotape by her daughters, Joanne Ashe and Pepi Strahl

(Excerpted from My Story, February 2023, Vol. 29)

”  I was born in 1924, on January 16, in Tarnopol, Poland. I had two sisters and two brothers. We were all two years apart. My sister, Regina, was two years younger than me. She was very sweet. lssua didn’t want to study. Hannale was younger, and Shulum was the youngest. We lived in one house, together with my grandparents, my aunt and uncle, and their children. It was a beautiful life. My other grandma and grandpa lived a few houses down the street. I had a lot of aunts, uncles and cousins throughout the city. Tarnopol was a beautiful city and our family life was rich—we celebrated all of the Jewish Holidays.

I was born in 1924, on January 16, in Tarnopol, Poland. I had two sisters and two brothers. We were all two years apart. My sister, Regina, was two years younger than me. She was very sweet. lssua didn’t want to study. Hannale was younger, and Shulum was the youngest. We lived in one house, together with my grandparents, my aunt and uncle, and their children. It was a beautiful life. My other grandma and grandpa lived a few houses down the street. I had a lot of aunts, uncles and cousins throughout the city. Tarnopol was a beautiful city and our family life was rich—we celebrated all of the Jewish Holidays.

My father, Asher Haras, was tall, dark, and handsome. He was not a serious man; he was fun-loving. He used to take me to the club to play dominoes. When l went into the third grade, I was very worried about the teachers being strict and mean, so I stopped eating. My father would take me to the store before school and buy me Halvah, so that I would have something in my stomach. He was warm and loving, and not as religious as my mother. He had a fabric store and I helped him, even though I was only 10 or 11 years old. Once a week, my parents went by horse and buggy to a flea market to sell their fabrics. They would travel all night to be there in the morning, and I would stay behind to look after the store, which was really a little stand.

My mother would do a lot of preparation for Shabbat. She would bake rugelach, challah, cookies with poppy seeds, potato kugel, gefilte fish and chicken soup with noodles. We invited a poor person to eat with us each Shabbat, even though we were considered poor ourselves. We had no electricity, and there was only a coal stove for heat. Winters were so severe and frozen that we often could not see out the windows. The toilet was outside and it was always frozen. The water was also brought in from a well outside, and the well woman would often sleep in the kitchen on a bench by the fire.

Every Saturday in the summer, my father took the family for a walk to the river. It was very beautiful and one of life’s simple pleasures. At night, when I got a little older, I would go walking on the boardwalk with a girlfriend. We would watch the most beautiful and stylish girls. I tutored three children for about $5 a month. I loved to read romance novels and stories about the Renaissance and the French Revolution. I was 15, and very pretty.

There was a lot of antisemitism at this time, and my father used to get beaten up a lot. In 1939, when I was 15 years old, the war broke out in Poland, and Tarnopol was occupied by Russian forces. In 1941, the Germans occupied our part of Poland, and life became a living hell. Every day a member of our family was taken away and we never saw them again. One day there was knocking at the door, and we knew it was the Gestapo, so my parents went into hiding with my brother and sister. I had working papers, so I stayed in the house with my grandparents, because they were too old to run. The Gestapo kept knocking and I had to open the gate. They came in and ran around the house looking for people. They ran upstairs to where my grandparents were still in bed and they told me to get them out of bed. They were pushed down the stairs, still in their night clothes. I still remember my grandfather saying, “Let me say goodbye to my children.” They were just kicked, beaten and taken away.

Also, while I was still living in that house, my mother’s father, Aron Lindeman, lived with us and the Jewish Police (Judenrat) said that they wanted to take the elderly to a nice nursing home, so they should get dressed in their nicest clothing and be ready to go. As it happened, the next morning when we went to the synagogue, we saw elderly people on big trucks covered in blankets and on top were machine guns. They took them to the woods where they were shot.

I was about 17 years old when the Germans rounded up a lot of young people to go to work. I was working for the German Army, cleaning their apartments. Then one day I was sent to a big warehouse at a railroad station. There were hundreds of people working in that place. A German officer was walking around with a very mean look on his face. He called me to come to him. I started to shake, and I didn’t know what he wanted. He asked me, “Do you know German”? I said, “Yes.” He said, “Okay, then you are going to work in an office.” Well, to tell you the truth, I was relieved. His name was Kurt Dietrich. I was the only Jewish girl working in the office. There was no money exchanged, only paperwork. The office was located at the railroad station where they had big warehouses of goods—blankets, towels, salt, sugar, etc.—for the army.

At that time, my parents were in the ghetto. I still had my mother, father, two sisters and little brother, and one brother worked with me at the railroad station. Once a week, every Sunday, we were allowed to go to the ghetto to visit with our parents. And of course, at that time, we didn’t have any telephones, so we never knew what was happening there. We didn’t know who was still there or who had been taken away and killed that week.

One time, during Purim of 1943, “the butcher” of the region, named Rokita, who used to walk around randomly shooting at people, came to our camp and told everybody to line up on the platform, separating women from men. After looking at everyone, he chose three girls. He pointed to me and two other friends of mine, and he told us to come to his quarters in the ghetto. Well, I didn’t know what this was all about. When I got there, it was unbelievable. Somebody was playing the piano and there was so much food that I couldn’t believe it.

Everywhere people were starving, and in his quarters, there was everything—meat, fruits, vegetables, you name it, and they had it. This was the most frightening thing I went through during the war—spending an evening in the house of this butcher. He occupied the nicest apartment in the city of Tarnopol, where a Jewish family used to live. He thought he would have a lot of fun with us. He poured different kinds of liquor, and every time he drank, he poured a glass for me and the other two women. I was sitting near a plant, and each time he poured a drink for me, I poured it into the plant when he wasn’t looking. And that was very smart, you know …

But then he said to us “We all have to go to different rooms, and each of you will stay here overnight.” I thought, “My God, what is this? I’ll never get out from this place alive!” I was really afraid that this would be the end of me. I was sent to a bedroom and told to undress. Lying on top of the bed, still in my clothes, I waited for a man responsible for tens of thousands of murders and shook when I heard him enter the room. When he approached me, I told him “I am sorry, but I just got my period.” He left the room, thank G-d.

One time I came into the ghetto, and people were saying “They are going to round up the Jews again. Why don’t we go into hiding?” In this house where we lived, they built a bunker underground. And we all walked in there. It was a very narrow passage. There was no air to breathe, and I remember how crowded it was. It was like going into a chicken coop, you could hardly breathe in there. My little brother was holding onto me, and that time, the Gestapo didn’t find us. We survived, but we could hear them walking all through the house, banging on doors and shouting, but they didn’t find us.

A few weeks later, when I came back to the ghetto, my father said, “They took away your mom, your little brother and your sister.” It was a Sunday. Now, I only had my father and one of my sisters still in the ghetto. Shortly after that, I decided to escape since my mother was gone, my sister and a brother, and there was talk that the Nazis were going to liquidate all the Jews in the city.

One day when I was working—it was June 9th, 1943—my boyfriend came to see me. He had taken his star off and came to my place of work. It was lunchtime, and at that time I had just gotten a different boss in the labor camp, an obnoxious guy who made the girls look at pornographic photographs. But he also happened to be away, so another man took his place, and he was not too dangerous. It was during the lunch hour and I noticed that a train had stopped and Russian people were coming out onto the platform for water. One of my friends came over and asked me, “Do you have a coat?” I said “Yes, but why do you need a coat?” “Because I want to escape—I want to run on the train together with those Russian women.” I said, “Okay, here is my coat. You can take it.” Then a few minutes later she came to me and gave me my coat back and said, “I don’t want to go.” I said, “Well, if you don’t want to go, then I will go.” Just like that. It was on the spur of the moment that I decided when the Russian women will go into the train, then I will go in with them. Once I decided, I joined the crowd of Russian women and walked onto the train, which was a cattle car. I had nothing to lose. You know, sooner or later, we all would be killed or sent to a concentration camp. I just had a summer dress on and a raincoat. I still wore my yellow star.

My brother was standing near me on the platform, so I gave him some jewelry that my father gave me in case I needed to save myself. I gave him everything except for my mother’s watch, and he gave me a loaf of bread. That was the last time I saw him.

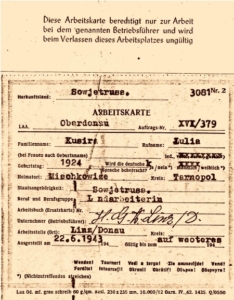

But then I realized, “What did I do”? Where am I going? I don’t have any papers or anything.” But it was too late to get out of the train because the German SS was standing in front, on the platform. I noticed that the Russian women all looked different. They all wore long dresses, and their hair was braided. So, I took off my dress and I pulled it down to look like a long skirt. I wore my raincoat over it and tied it with a belt. The train started moving and I immediately realized that I had to think of a different name, one that sounded Ukrainian. I looked out of the window and saw a goat, which is kuzi in Ukrainian. I named myself Julia Kusira. I was determined not to be a Pole but to be Ukrainian because the Polish girls are mostly blonde and I was a brunette. I remember going through the city of Lvov and on to the town of Przemysl, where everybody had to get out and be strip-searched and examined. And at that time, I was given a number.

After being examined in Przemysl we got back onto the train, and I saw that many of the Russian women had discarded their clothing. I picked up some clothes and dressed myself as a Ukrainian. I looked like a beggar. In Przemysl, I noticed that there were other Jewish girls that I knew from the camp who had also escaped. One of them had been a good friend of mine, but nobody wanted to talk to each other. They didn’t want to be conspicuous. I also didn’t know at that time where the train would stop. After a few days it stopped in Linz, Austria. In Linz they put us all into a big camp. There were thousands of people from all over Europe. There were people from Greece, from Yugoslavia, Romania, from Hungary, and Czechoslovakia. It was from here that people were assigned places to work. I was taken to the Gestapo because I did not have any identification papers. I had to make up a story as to why I was on the train together with Russian women. So, I told them that I was on the street when they were rounding up the Russian women for work in Germany. I was just caught in the crowd of women and pushed onto the train. That’s why I don’t have any documents. I begged them not to send me back because all of my life I wanted to come to “beautiful Austria!” I told them I would write home to my parents and ask them to send me my documents.

I was standing in line to get some food, and I saw a young man staring at me. I said to myself “Aha, he can see that I’m Jewish!” So, he came over to me and he said, what are you doing in this group of Russian women? And I thought to myself, “He knows.” I said “Why, what do you mean?” And he said, “Well, you look just like typical Polish aristocracy.” I said that I was, and then I told him that my father was a Polish officer and when the Russians occupied this part of Poland, he was sent to Russia. Then he said to me, “Well, I’ll have to see you a lot now since you’re here. Get away from the other Russian women, you don’t belong with them. You’re a typical Pole.” And he wanted me to go meet his sisters. I thought, “Oh, my God, that’s all I need now is to get involved with a Polish guy.” I couldn’t get rid of him, so I decided, “Okay, I will go.”

I found his two sisters somewhere in one of the houses. When I came in, they were both kneeling and praying. I had no idea about anything having to do with the Christian religion. I didn’t even go to a school where any Christians were enrolled. I went to an all-Jewish school. I had no idea about praying as a Catholic. I just kneeled and I pretended to pray like them. Luckily for me, the very next morning they shipped him out somewhere, and that was how I got rid of him.

I was eventually sent to work in a huge factory called Hermann Goering Reichswerke. There were a lot of people from Europe working there, mostly from Poland. I was afraid that someone would come in and recognize me. I thought, “I will never survive here! It’s impossible among these Polish people!” I frequently used the excuse of having headaches, and I would go to the infirmary, where I would say, “I can’t stand the noise in this factory.” They would give me pills for the pain. One time, while I was examined by a doctor in the hospital, he said to me, “Why don’t you work here in the hospital?” I said, “Well, I can’t choose. I have to go where they send me.” I was always worrying that with so many different people coming to work there, that someone might recognize that I was Jewish.

After a while, I was moved to the hospital, which was very lucky, because at the hospital, I was just taking care of the chief of the hospital’s office and the operating room. I was not in touch with so many Polish people. I felt that this was a much safer situation for me. The people who worked there lived in barracks and I was free to go in and out whenever I wanted. I was not in a camp. I lived there with 10 women. They were from all parts of Europe. As it happened, there were two girls from Poland, actually from my hometown, but they didn’t know me. They were typical Polish, peasant girls, and they said to me, “How come you speak so differently?” I said,” Well, I’m from a big city. You are from a village.” They respected me. They never let me even wash the floor.

Every minute of the day I had to be somebody else. Whenever I was in this hospital and somebody spoke to me in Polish, I pretended that I was Ukrainian. It depended on who came in and who talked to me. While I was at this hospital, they said to me, “We need nurses. Why don’t you be a nurse? We will train you.” I said, “Oh no, I’m too stupid. I just don’t understand anything. I’d better stay and clean.” I just didn’t want to get involved. I felt that the less I showed myself, the less I would be involved with people, and the better off I would be.

I did everything possible to avoid talking to people. An Austrian woman said to me that her husband was in the army. “Why don’t you come and live with us?” I thought, “Oh my God, this couldn’t happen to me! How lucky to be staying with an Austrian woman?” I went to the police, and I registered. I told them I didn’t have any papers. I had to make up another story. I pretended that I had been caught on the street and they asked me, “How come you speak German so well?” I told them “My mother was a German teacher. She taught me German.”

From then on, I didn’t stay in the camp with those 10 women, but I lived with this Austrian woman in her house. I felt so secure because she didn’t know the difference between Jews and non-Jews. We used to go to the opera and to the theater. Imagine this! I was sitting in the opera house. Next to me were German Nazis, and I said to myself, “If only they knew that I am Jewish!” Later, I received a summons to come to the Gestapo, who were the Austrian police. When I came to the Gestapo, they asked me about my papers. I had to make up a story. I told them I was caught on the street and I had no papers. The officer in charge said, “Why don’t you write home?” I said, “Okay, I will do that.” I wrote a letter, and I sent it to an unknown address because I didn’t have an address. But I had to send it by registered mail just to have a receipt that I sent a letter to my parents. Each time I received another summons to the Gestapo. I would say, “Look, I wrote to my parents, I don’t know what happened there. Maybe the war is … maybe the Russians are back there. Who knows what’s going on there?” I said, “Look, you are worried about my stupid papers and I don’t even have a winter coat to wear!” After six months the Gestapo officer said, “Well, I’m tired of her,” and he turned to the translator. “Why don’t we just give her some papers?” They gave me official papers with my photo attached. They said, “We are writing that you are a Russian.” In that moment, I was so happy and relieved. I started to cry, but he didn’t know why I was crying. I said, “Russian!! How can you insult me like that? I will show you who I really am when the war is over!”

Eventually, I had to go back to the camp where the 10 women were. They were all antisemitic. I used to come from work and go straight to bed and pull the covers over my head, because they were reading letters from home about what they were doing to the Jews. One time two of the girls approached me and they said “Oh, you look like you are a Jew, and you’re trying to be someone else.” I laughed at them, and I said, “Oh, no, are you crazy?” But at the same time, I was afraid that they were going to the Gestapo and they will tell them that I’m a Jewish girl who escaped and is trying to pretend to not be Jewish. At that moment, I decided that I had to leave the hospital and escape. I decided to get on a train again and to go to Vienna. After the train had traveled a few miles away two Gestapo men came to ask everybody for papers and passports. Naturally, I didn’t have a passport. They asked me where I was going, I said I was going to Vienna. They sat down and they pointed their guns at me. Upon arrival, they took

me away from the train station to the police in Vienna. At the police station in Vienna, I convinced them that I was on leave from work, although I did not have papers to prove it. I flattered them, praising their beautiful city, mentioning how far I’d travelled to see the Schoenbrun Palace, the Opera, to walk in the Prater Amusement Center, and to eat their delicious pastries. And that was my first day in Vienna. There I was. I didn’t have a place to stay. I didn’t have a place to work. I didn’t have money, just a few shillings. The first night I slept outside in the street in a telephone booth. When you step in the center of the booth, the light goes on. I couldn’t keep stepping in this center. I had to stay like this with my legs apart, the whole night long. In the distance, I saw the police. I was lucky that they didn’t come to make a telephone call.

In Vienna, I had a girlfriend who escaped at the same time as I did. When I came to see her, she saw me and she thought she was seeing a ghost. She said, “Keep away from me. I am scared out of my wits! I’m working for this Gestapo family. Please don’t come near me! I’m afraid that they will see both of us together and see we are both Jews.”

There I was. without a job, without a place to sleep. In the morning I went to a coffee house, and I said to the woman there, “Would you know a place where I can sleep? I don’t have money to go to a hotel.” She said, “Oh yes, why don’t you go next door? There are a janitor and his wife, and maybe they will let you stay there.” They were an elderly Austrian couple with a nice apartment in the basement. They said I could sleep there and asked me what I’m doing in the middle of the war in Vienna. I said, “Oh boy, I have a boyfriend here and I’m so much in love with him that I came to see him.” During the day, I used to go to a work camp where they assign people jobs. This office was located on the outskirts of Vienna. As I was walking from the streetcar to this camp, a young man looked at me and started to flirt with me. I ignored him because I just didn’t want to get involved with anybody. I saw in the distance a group of people with yellow stars. I thought, “What are those Jews doing here?” And I knew if I would walk by this group alone, I would either fall apart or get recognized. I was afraid, so I walked over to this young man and I started to flirt with him. And I said, “Oh, come on, let’s go have breakfast.” I told him to talk to some of the people in the group and find out where they were from. They told him they were Jews from Hungary.

After seven days I was sent to clean an apartment belonging to a Viennese woman. On her nightstand I saw a Jewish prayer book. I panicked and decided that I had to return to Linz. I also had a bad infection on my finger but I couldn’t go to a hospital in Vienna.

Back in Linz, it was Christmas time, and I didn’t know what I was going to do. The Polish girls in the camp wanted me to spend Christmas with them. And I was afraid that I didn’t know the music and customs So I told them that I was invited to an Austrian family with my boyfriend. And when the Austrian people asked me to spend Christmas, I said, I’m invited to a party with my other friends. Instead, I bought a streetcar ticket, and I was riding from eight o’clock in the evening to midnight from one end of the city to the other. There were two guys on the streetcar and they were saying to each other, “Look what happened to our beautiful Vienna! We have all the nationalities here now, even Spanish people.” One of them asked me if I was Spanish. I said, “Si, si, señor,” and I jumped out of the streetcar. Every minute, I had to think of something. When I got back to the camp, everyone was sleeping.

Those two years were a living hell. I was afraid every minute of every day that I would be discovered to be a Jew. One day, I came into the dining room and a Ukrainian woman said to me, “You know, you look just like a Jew.” I said, “If I look like one Jew, you look like 10.” But in the meantime, my legs were shaking. I had to always be prepared with what to say to whom just like that. I could have been anyone, a Polish aristocrat, a Ukrainian peasant, a Volksdeutscher, a Spaniard, yet I was a frightened 19-year-old Jewish girl from Eastern Europe playing the game of ‘Aryan,’ acting a role without a script or even acting lessons. The truth was that when I was growing up, I never left my home, I never traveled any place and I went to a Jewish school and lived in a Jewish neighborhood. I didn’t know anything about being Christian. But I knew how to speak several languages and that certainly helped me to survive!

In May, 1945, the American Army came to Linz and the war was over. That was a very sad day in my life because now I was alive and I knew I had no one. But I stayed in the hospital and I didn’t go back to the camp. I went back to the same Gestapo policeman, who used to question me because I wanted to get my name back. And I said, “Mr. Prakowski, you were always wondering who I am. Now I can tell you I’m Jewish.” And he said, “What? But why didn’t you tell me? I would have helped you!” Can you imagine? He would have sent me to Auschwitz!

A survivor from Mauthausen, named Maurice Strahl, came to the hospital with sick people from the concentration camp. He was assisting at the hospital. A Polish doctor said to him, “Here, come meet my little Polish girl.” Maurice took one look at me and he said, “You’re Jewish.” I said, “No, I’m not Jewish.” I was still afraid to tell anyone I was Jewish. But then I turned around and said to him “Oh yes, I’m Jewish.” He said, “You don’t have to be afraid. The war is over.”

I told him which of the nurses was the worst, and he put them all to work in the typhus wards. They were screaming and crying that they had children at home, and he told them, “I had a family once, too.” I ended up marrying Maurice a few months later. I always said that Hitler was the biggest matchmaker in history because, after the war, we gravitated to whoever was left to begin our lives again and start new families. “■

Clara Haras Strahl

Sometime after the war, Clara heard that every Jew who remained in Tarnopol was gassed on June 20, 1943. She had escaped 11 days before her ordained death. Clara and Maurice Strahl married in Linz and eventually immigrated to the United States and settled in Beverly, Massachusetts, to raise a family. After their grown children moved to New Mexico, married and raised their own families, Clara and Maurice followed. They spent their last years among their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren in Albuquerque.

Comments

susan seligman

Jennifer Fischer

c.fisher

Karen Kravetz Gaines

Jennifer Fischer

Kim Larson

Patricia Kurz

Susan Seligman

Jill Shaw Ruddock

Mollie